Every spot in this food hall is a must-hit.

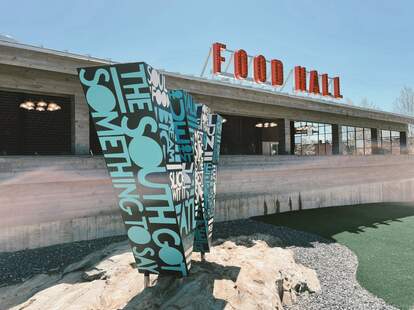

Chattahoochee Food Works exterior | Photo by Via Failla

Chattahoochee Food Works exterior | Photo by Via Failla

Chattahoochee Food Works opened its doors mid-May in Atlanta’s Underwood Hills neighborhood. The 31-stall food hall resides within The Works, an 80-acre complex along Chattahoochee Road. With 15 of the stalls already open (and more opening soon), the food hall has an energetic buzz about it right as they start serving food at 11 am. While The Works is beautifully designed, and there are plenty of reasons to visit it, including Les Mains Nail Bar and Ballard Designs, it’s the food hall and its tenants that most make it an exciting destination. As we come out of the pandemic, CFW is showing that food halls are still a promising fixture of the dining landscape for both diners and business owners.

In the thick of the pandemic, people wondered what would become of food halls. The stalls are close quarters and the halls invite people to congregate inside making social distancing difficult—two no-no’s when up against COVID-19. It’s been two years, though, since the inception of the 22,000-square-foot CFW, which is backed by Robert Montwaid of Gansevoort Market in Manhattan and the forthcoming Dayton’s Market in Minneapolis and Andrew Zimmern of Bizarre Foods fame. They started permitting the project and selecting vendors in March 2020 right as the pandemic hit.

But Montwaid believes that the business model of food halls will be even more tempting for fledgling restaurateurs coming out of the pandemic. “It’s a great business model because we take care of all of the operational aspects such as electric, gas, pest control. It’s all combined into their one check that they write, and we let them concentrate on creating the best product they can,” says Montwaid. At a time when restaurants are facing labor shortages in addition to a host of other issues being exposed, food halls still provide a lower barrier of entry to the restaurant industry.

Sai Untachantr, co-owner of TydeTate Kitchen agrees. Before opening in CFW, she and her family ran their Thai catering business out of Lawrenceville and gained a following by doing pop-ups. When they were ready to grow, the idea of opening a stall in the food hall was exciting especially because it’s the first of its kind on Atlanta’s west side, and opening a full-service restaurant, especially right out of the pandemic, wasn’t appealing to her and her family. “I think this is what we are liking more, it’s not such a huge space. It’s a perfect square footage,” she says. “A full restaurant would be a lot to handle. People just come and there’s so many options and it’s just a great place to hang out.”

When it came to curating the stalls, Montwaid hit the ground running and ate his way around Atlanta, chatting with people about under-the-radar chefs. What sets his markets apart, he says, is the fact that they are about 90% owner-operated. Everyone at CFW is based in Atlanta, and many of them are newcomers (with certain exceptions, like Morelli’s Ice Cream which is an Atlanta institution). “It takes me a little longer to curate my markets, but I think the end result proves to be worth the time and effort. We have mothers with children operating vendor booths, we have married couples, and we have individual owners,” says Montwaid. Other stalls in CFW include Taqueria La Luz, Sakura Ramen Bar, and Baker Dude, with more on the way, including a third location of Belen de la Cruz Empanadas and Hippie Hibachi.

At the Graffiti Breakfast stall, husband and wife team Tonya and Marcus Waller serve up southern breakfast dishes with flair like waffles stuffed with blueberries or catfish with blue grits. Marcus has been a chef for over a decade and worked in a range of kitchens from upscale King + Duke to Waffle House but has long dreamed of owning his own place.

There’s no way he could have opened a brick and mortar restaurant, says Marcus Waller, who started Graffiti Breakfast as a pop-up. Beyond finances though, the biggest appeal of opening a stall in CFW was the community he found with other vendor owners. “These are my homies, you know what I’m saying? These are my homies and my homegirls. We talk about food all day long,” laughs Waller. He describes how the tenants help each other out, whether it’s through sharing advice or ingredients. “The place is beautiful and the ability to actually make some money was great too. But mostly it was the family atmosphere of this place. We are really, really cool,” he says.

Other vendors find value in starting small while getting their feet wet. At Monster Cravings, Veronica Dalzon whips up dreamy cookies in flavors like strawberry shortcake and s’mores (she even toasts the marshmallows to order). Dalzon’s passion for cookies came along in 2019 when she was battling grief born from personal tragedy. “Instead of soaking in that pain, I just started an Instagram with cookies, and I was like, ‘All right, let’s see where this goes, and just grew my business from there,” says Dalzon. She hopes to eventually run a cookie empire, but is starting with her stall at CFW. Being there has given Dalzon a chance to learn the ins-and-outs of running a scaled-up business. “I had to learn to accept help and learn how to delegate that help. So, that was a really big learning curve, but also learning new machinery, so that way I can produce more,” says Dalzon. “I’m still having to produce more and revise my recipe to allow for more production, because not everything is just one-on-one.”

If the pandemic taught us anything it’s that no one can truly predict the future of anything—much less food halls. Now that people are congregating indoors again, there doesn’t seem to be much concern about whether the chefs at CFW will find success. But for chefs like Marcus Waller, the chance to find out is everything. “All of us (chefs) were so dead without being able to cook during the pandemic,” says Waller. “And now that we have this opportunity, it’s like, no man, we’re never going to forget what happened during the pandemic, because this is what we do.”